Beware of Darkness

John Haberin New York City

Lorna Simpson: Gathered, Darkening, and Ice

Lorna Simpson will always have me humming along but unable to sing. It is my fate, as a white male standing apart from the black men and women in her art. It is their fate, too, in her 2001 video grid of lips humming "Easy to Remember," by Rogers and Hart. That video attests to the urgency of memory in a country still marred by racism. It also attests to the studied reserve in much of her work, just as one will never see the entire faces. I kept encountering it in an earlier review of Simpson at the Whitney in 2003 and, four years later, in retrospective.

Still, she was taking the viewer all along into private lives, including the daily routines in a video calendar. Could she be losing much of that reserve herself? Here I follow her first to the Brooklyn Museum, with her own additions to found photographs and lost memories,  then into paint, and last into the cold. A dank chill has descended over painting everywhere since the pandemic, but nowhere so much as with Lorna Simpson at the Met. Just to enter black America through her latest art is to breathe the arctic air and to feel the arctic ice. It is to be up to one's neck in crystal blue arctic waters.

then into paint, and last into the cold. A dank chill has descended over painting everywhere since the pandemic, but nowhere so much as with Lorna Simpson at the Met. Just to enter black America through her latest art is to breathe the arctic air and to feel the arctic ice. It is to be up to one's neck in crystal blue arctic waters.

Hard to remember

For Lorna Simpson, the black middle class has a history—more often than not a woman's history. In one video installation, she imagined a woman navigating the duties and confines of an early American home. The woman could have been seeking a life or trapped in one. She could look forward to the woman in a second projection, at home in a classic of modern architecture. Simpson described the first as a fugitive slave in the moments before recapture, but one might otherwise never know it. All one can say for sure is that simple pleasures come with forgotten stories, and both are easily snatched away.

For Simpson parallel lives do not easily meet. They include days spent on the phone or filling the spaces in a calendar. She identifies with them, but they would not be half as poignant or as distant if she could not leave herself out of it, give or take a sometimes chilly inscription. Or so it seemed until 2011 in Brooklyn. With the photo sequences in "Gathered," men and women pose for themselves as well as others, although others may still have the last look and the last word. This time, too, she allows herself to appear.

She again mixes staged and found work, from flea markets and eBay, and she again juxtaposes past and present. An alcove also has her Easy to Remember, because African American stories are all too easy to forget. One long wall has well over a hundred photographs, from 1957 in LA. Mostly women, the models pose in the seductive conventions of fashion and style shoots. The facing wall has head shots from old photo booths. Yet Simpson doubles the first, and she intersperses tiny framed sketches with the second.

She has allowed herself to be drawn in, and the change is striking. It did not come all at once either, and with accretion comes a greater spontaneity. One can see it in the titles of successive additions. The series began with a demand, Please Remind Me of Who I Am. They continued with Instantaneous, Standstill, and finally just Untitled. The urgency of the title first masks the greater detachment, while the increasing silence allows anonymous lives their say.

Did I expect a firmer and harsher commentary, as so often in the past? Did I imagine a forced march through nearly four hundred paired images, with the present always having the last word? Instead one sees the past shaping the present and the present learning to remember the past. Black was already beautiful, they say, and a man at a chess table is a lot more dapper and funnier than hustlers in Washington Square. Memories of Jim Crow are poignant now? And yet the smiles in the photo booth are their own.

Rather than simple imitations on one wall, one has themes and variations, and they are rarely side by side. Each wall forms a single large work—rising and falling, swelling and narrowing. Simpson in fact describes the smaller work as a "cloud," and one can see the abstract ink stains as clouds. They also evoke old photographic plates exposed deliberately or accidentally to light. The notion of exposure still runs through the series, as a critique of American culture in black and white. At the same time, she hopes, exposure is rediscovery.

Is she really painting?

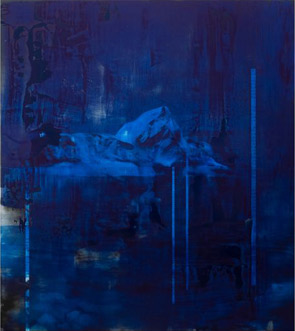

Simpson was opening up a dialogue even before her videos with sound. Some silkscreen cityscapes of the late 1990s, with felt panels for text, soften the message in a different way. Still, they oblige one to puzzle out even the obvious. And she still does, only now that means penetrating the darkness. She even calls her latest work "Darkening," and there is more now than ever to penetrate. They open onto vast arctic seas in paint.

Is Simpson really painting? She made her name with photos paired with text, but even her videos border on conceptual art. Now a dozen big blue canvases combine silkscreen and paint, and it is hard to know where one ends and the other begins. It takes paint to make a silkscreen, and she lets it smudge and blur, for its own sake or for clouds and sea. Every so often it leaves exposed the white ground, sometimes in vertical bands that contain words. If the big blue recalls Onement by Barnett Newman, the words could be his "zips."

Is Simpson really painting? She made her name with photos paired with text, but even her videos border on conceptual art. Now a dozen big blue canvases combine silkscreen and paint, and it is hard to know where one ends and the other begins. It takes paint to make a silkscreen, and she lets it smudge and blur, for its own sake or for clouds and sea. Every so often it leaves exposed the white ground, sometimes in vertical bands that contain words. If the big blue recalls Onement by Barnett Newman, the words could be his "zips."

The sheer scale recalls the Hudson River School—and towering icebergs an earlier sublime in Northern Romanticism and nineteenth-century Danish art. Still, another kind of glamour altogether slips in. One or two superimpose a black fashion model, in purples that deepen and enrich the blue, while smaller paintings overlay faces on one another, like a Cubist Ebony. A tall stack of magazines holds the center of the gallery as Simpson's Timeline. She describes the series as taking considerable research, but that, too, might have been a guilty pleasure. If Andy Warhol had taken up the Abstract Expressionism, he might have found himself here.

Simpson would be the first to protest the association. She has worked with found photos long enough, thank you, and the felt was large, too. For several years now, she has also combined photocollage and paint, with color additions to images of woman. When she called one of those paintings Blue Wave, the wave meant a woman's hair. Now light glistens off icebergs and distant skies, with no obvious source in the dark of night. Asked if the scale of her new work signals its ambition, she prefers to think of it as a loosening and a space for her to explore—not unlike an arctic exploration after all.

Is she, then, extending her old concerns, now to blackness and the blues, or deconstructing them? Instead of acid commentary, her pillars of text amount to mere fragments of words. (I believe I could make out "children" and "thieves.") Pop Art made use of images and text, too, but filled with advertising's impersonal desires. How far that seems from Glenn Ligon in his coal-spattered power slogans or Simpson's own raw cultural history. How far it seems from these words as well.

Feeling the chill

The Met does not stick to Simpson's Ice paintings, but the rest is no less bleak. Touches of yellow and those wide-open fields of blue cannot remove the weight of a meteorite descending from above or still more ice emerging from below. Their monotone grays do not compete with the touches of color, but rather add up to a single icy palette belonging equally to photographic prints, the artist, and life. A young man and a glamorous woman wrap themselves in it for warmth. They have little choice. They wrap themselves in the mists and masses as well.

It is not quite their only recourse. That wet space beneath the heavens gets along just fine with a truly dry sense of humor. Simpson plays with the scale, drips, and black squares of abstract painting, to laugh at it like a proper Postmodernist, but also with it. Her Gradient and Special Characters series take the measure of violence in America, whatever the temperature. Black circles are at once bullet holes and the pattern on a polka-dot dress. The new African wing of the Met begins right outside, past a gift sheet, but it could be a continent away.

Simpson has put her sharp wit and deep feelings on display often enough before. Born in 1960, she had a Whitney retrospective in 2007, projects at the Brooklyn Museum in 2011, and regular shows at one of Chelsea's poshest galleries. Is there really a need for more? The curator, Lauren Rosati, speaks of a more comprehensive show than any before it, but I am not so sure. Want to be the first to cover every stage of an artist's career? Just wait until a little time has passed since her last show.

Not to confuse you with facts, but the Met has barely thirty works, most from a decade ending in 2021. It is no less timely for that. Where African American art used to mean African American history, scathing or supportive, recent shows have followed artists to Africa to recover a heritage. Simpson takes the logical next step. Why not leave the dark continent behind in favor of bright silkscreens and collage—and a hot continent in the midst of global warning for ice sheets? You can find a reality check in style magazines when you get home.

In fact, Simpson found her images and image makers in Ebony or Jet. That includes a woman with cat whiskers, a frisky smile, and a leopard-skin dress accompanied by a leopard with a wholly human smile. She turns stacks of those publications into sculpture as well, with a pretend ice cube beneath them. It may be a bit large for a drink and small for an iceberg, but The Titanic is safe. Just ignore the museum's careerism in favor of its art. Simpson has what it takes to stay warm, the black community.

As I wrote after her retrospective, she refuses to play black artist while insisting on what the universal leaves out. Even now, as I wrote after her Brooklyn projects, she wears away at the boundary between the personal and the political (and you can follow the links to my past reviews for more). Her characters may talk, but they do not so easily communicate. They can let down their guard for a moment, but someone or something dangerous is about to interrupt, maybe the viewer. They can carry a tune, but it has to be easy to remember—or at least "Easy to Remember," by Rogers and Hart. They can hum or whistle, but it is up to art to sing.

Lorna Simpson ran at The Brooklyn Museum through August 21, 2011, at Hauser & Wirth through July 26, 2019, and at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through November 2, 2025. An earlier article looks more fully at Simpson in retrospective.